CELLULOID STUDIO

Emma Forrest

2026

When looking at paparazzi pictures of Golden Age stars caught in moments of decline or humiliation I am reminded of religious frescoes ruined by cack handed worshippers. Handled incorrectly, Jesus Christ becomes a monkey and the Virgin Mary a reality show contestant. These ruined frescoes (as with the garish celebrity snaps) leave worshippers aghast because we know that’s not at all how Christ or Mary or Judy Garland are supposed to look; not if we are to project our dreams onto them.

I made the connection during my time spent with this exhibition. Studying Nina Mae Fowler in action, I understood that what moved me was her pain staking restoration of those hallowed figures who have been despoiled by others. This is the crux of Fowler’s work - her pencil detects the kernel of who is really in there, who was always there, the true soul before and after life’s obstacles. If those National Enquirer magazine covers depict a kind of “locked in syndrome”, then Fowler becomes a translator. Using pencil and paper, she clarifies voices slurred by Dexedrine prescribed in childhood or alcohol for stage fright or garbled by oppressive studio contracts. She speaks both for those depicted and for herself; her work simultaneously biography and autobiography. Are you worried you will go mad? That you have been? That you are now domesticated but there is a trap door in your mind you could fall through again? The artist is and so is her ideal viewer.

“It's clear to me that I relate to my subjects” says Fowler, “it's the same part of me who drew her idols aged 10, simply out of adoration, that is still doing it 34 years later. But my reasons have become loaded with experience and time.” Her pieces echo the feeling we get on the traditional Mexican holiday ‘Day of the Dead’, the one time in the year when the veil between the living and the deceased is thin enough that the dead can make themselves heard by those who long for them.

Years ago, touring an exhibition at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe, I found the Navajo section had, before entering, an announcement from the tribal council saying these pieces were never for your eyes, the Navajo do not want you to look at their artefacts and if you do so, it is at your own risk. Because ‘Celluloid Studio’ is so incredibly vivid - shot through with fury and resilience - Fowler’s work commands the same sense of danger. Have you the fortitude to look with her at all of someone and not just the shiny surface?

Studio View

The largest picture here is of the renegade actress Susan Tyrell and takes up an entire wall, 3 metres wide. Nominated for the Best Actress Oscar in 1972 for John Huston’s ‘Fat City’. Tyrell fled almost directly from the awards show to Morocco for two years, disappearing from the spotlight and “squandering” her hot streak. It was only some time later in 2000 she went on record about the power dynamic between her and Huston and the inferred sexual abuse that took place during filming.

The juxtaposition of drawings in Celluloid Studio invites conversations between generations, solidifying the endurance of Fowler’s themes of womanhood and pain. On one wall is a drawing composed from a 1970’s paparazzi shot of the Hemingway sisters - they did not get on and Mariel’s star was rising as Margaux’s was fading, alcoholism kicking in. It is a call and response with the drawing of 1940’s Paramount starlet, Gail Russell, who died age 36 of acute alcoholism.

Russell began drinking to ease her stage fright and lack of confidence. The drawing depicts her arrest in the summer of 1957 for a drink driving offence - the meticulousness of Fowler’s work offers the viewer an opportunity to sympathise with her fragility/pain and, to my mind, her dignity is restored.

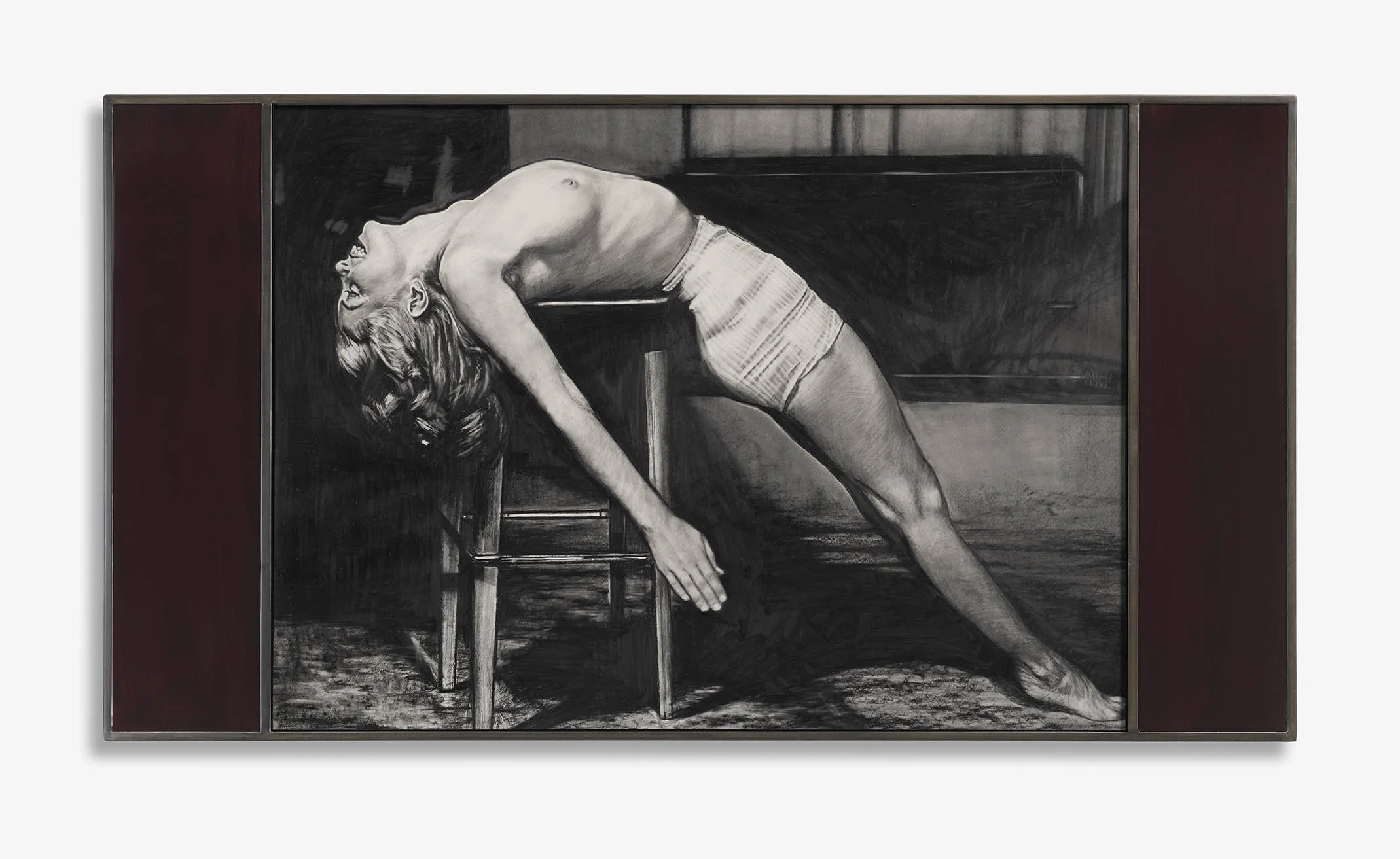

There is always a conversation between the moment portrayed and the manner in which it is recorded. Moments of thrashing impulsivity are rendered, painstakingly, by an artist whose pencils are nubs from attention to detail, whose rubbers are blackened from sheer physical labour. Fowler knows what every single snipped and warped rubber does. Her transmutation of the overwhelming mistakes celebrities make is a version of sitting in a bad feeling until you overcome it. People who get frequent DUIs can’t do it, but an artist in their remote studio, a landscape and many decades away, can do it for them.

One of my favourite recurring motifs in Fowler’s art is incredibly graceful people caught in a moment of ungainliness. Behold Nureyev dancing awkwardly with Sybil Burton. Nureyev, mid swivel, looks almost nerdy. So could it be that she’s the one who is the star in this portrait? This discarded first wife of a genius who found himself a real movie star, who projected his dreams onto a difficult person and had his greatest prize for all the world to applaud? Her? When I look at Sybil Burton here, in her post divorce life as a very successful nightclub owner, I think: are you your own prize? Therefore, am I? It is a humorous, heartening piece.

Glancing back at Nureyev one can’t help feeling amused: what exactly is the point of a spectacular dancer when they are not performing? Go from there to the depiction of Mikhail Baryshnikov and Liza Minelli at studio 54. Lovers, they are talking not with each other but at each other, posed at angles like the women in Abba videos. Fowler smiles, “There were chemicals involved, perhaps.”

I notice she has kept the party goers who happen to be caught in frame at the club and she explains they are there because “people in the background of photos represent us and make the Gods shiny. Compositionally I like them, as well. I could black them out, but then it’s just the relationship between the two stars - the other shapes give context.”

Track from here to Fowler’s portrait of Ballroom dancers backstage and one thinks of the Avedon photo of Marilyn Monroe caught, briefly on film, not performing for the camera, a far away look in her eye, her breasts pulling heavy on the sequins. (Speaking of Monroe, Fowler once made a frame based on a surgical tray in which to hang her drawing of Marilyn’s exit from hospital after her ectopic pregnancy). Frames are hugely important to her, as much a part of the piece as the drawing. After all, context is everything. Exploring the physicality of celluloid itself, each drawing here is flanked on either side by panes of glass painted the colour of celluloid film (a collaboration with her husband, Craig Wylie).

“He proved this colour could only be achieved with the depths of pigment in oil paint”.

She explains that “Celluloid is combustible, difficult to work with, expensive to produce and becomes brittle over time.... the perfect metaphor for my subjects”.

A lot of the pictures Fowler works from come from extensive research into film and photographic archives (she was offered the opportunity, for example, to access Marlene Dietrich’s personal letters to her grandson). At the other end of the spectrum, she has had luck sourcing images from charity shops. In one local shop, she found someone’s collection of lobby cards that she wasn’t quite sure how to use. She put them in her shed where they began to decay through water damage. Now they made the grade and are included in this exhibition as small promotional adverts, preserved in their decomposition, ruined in their finery and thus contextualising the elegant decadence of the rest of the work.

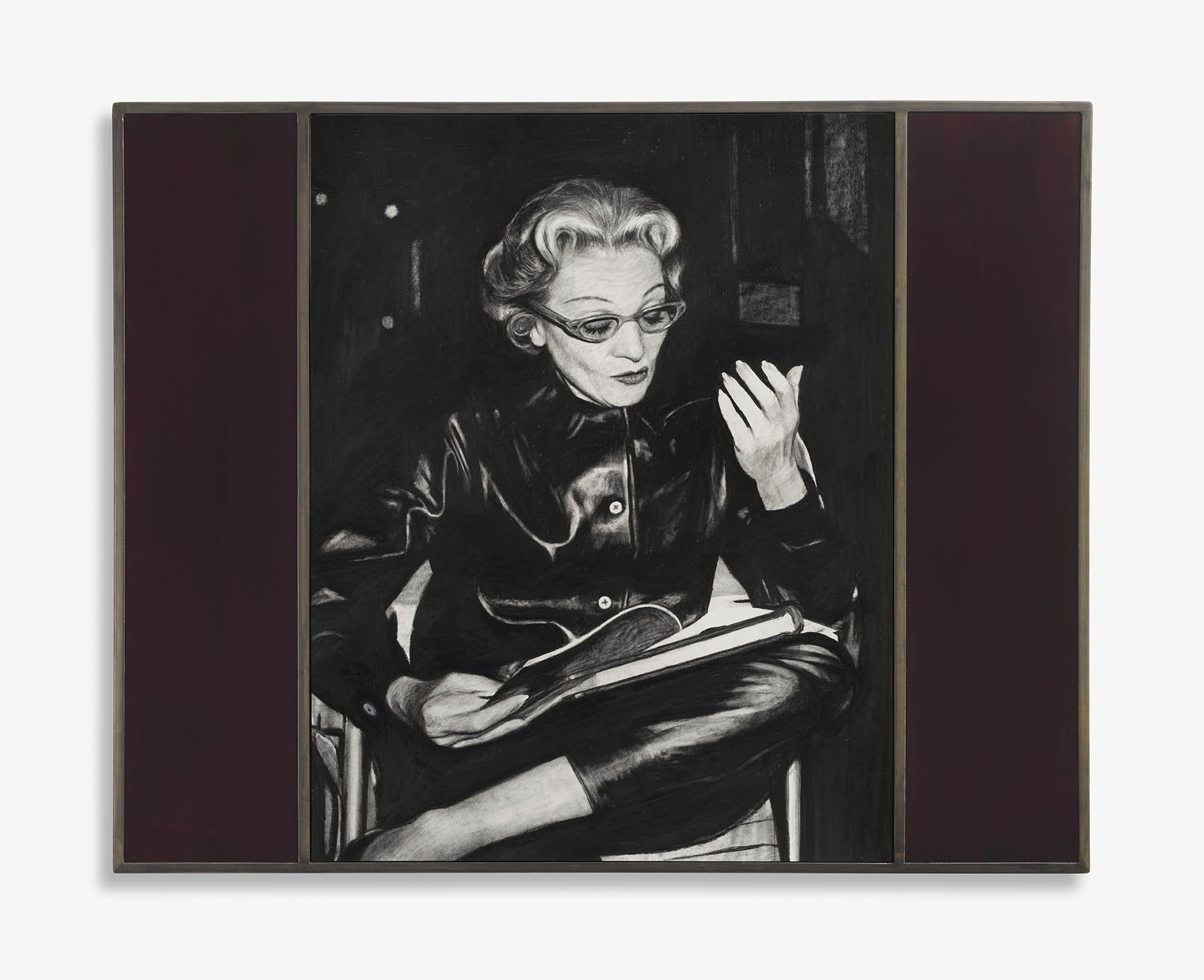

“The main thing when choosing an image is I’ve got to really want to draw it. A lot of these are images that I’ve lived with for a long time”. She particularly relishes the challenge of fabrics which is why the image of Marlene Dietrich here (to whom she is frequently drawn) is one in leather. Her images are created using 50% pencil and 50% rubbers. Her pencils are like a keyboard, from the hardest (which is darkest) to the lightest, and all the snipped rubbers do different things. “I know them all very intimately. They’re all doing as much work as the pencil. It’s practice, like a musician when you get to know your instrument so well you know what will give which effect.”

I feel dizzy watching the sheer physical exertion she puts into each portrait. I’m aware of the balancing of brain chemicals we get when we break a sweat, and wonder if, contrary to the cliche of the “mad artist”, Fowler is fostering her own sanity through this depiction of people living on the edges of it.

Not long before I visited Fowler’s Norfolk studio, I had been to Amsterdam to see Anne Frank’s annexe for the first time. I was struck that, in the tiny room she had to share with a middle aged male dentist, she had cut outs of movie stars pasted over her bed. Those images of celebrities soothed her, even when waiting for the sounds of jackboots, she had those idols…watching over? A way out? As witnesses?

With a BA in Fine Arts and Sculpture from Brighton University, maybe Nina Mae Fowler’s path as an artist was (talent aside) set by nominative determination. Her name sounds so much like a Golden age Hollywood star arrived, pure hearted, from afar, before they are given a new moniker and neurosis by a studio head. But it isn’t “just” glossy Old Hollywood you’re seeing when you look at her work - anyone who would say this is gloss has, at minimum, misunderstood the nature of her work. I am the same age as the artist and I recall as a child, loving Madonna and knowing that was all gloss. But that when I looked at Cyndi Lauper, I could pick out all the different fabrics and textures and how some of the things she was wearing would be cozy but some scratchy, some sweaty, some would have a smell of mothballs from the thrift store, there would be leaking Day-Glo hair dye in her frenzied dance. And that all of that was aspirational to me because it was a real, recognizable human.

Fowler is delighted to be exhibiting again in France, where she first showed her work in Lyon, 2009, with a full scale replica drawing of Rudolf Valentino’s funeral. She feels her work is understood in France. “They appreciate cinema in a different way, and faces, and melodrama”.

‘Celluloid Studio’ is composed of 24 drawings/frames, the frames hanging immediately side by side, it’s look inspired by the walls of an Italian restaurant, celebrating famous faces of a bygone Hollywood. “This is a subject my work is often mistakenly grounded in. I have leaned into this confusion”.

There are 24 images here because 24 frames per second is the standard frame rate for most motion pictures. This rate is achieved by displaying 24 distinct still images for every second of film, which is fast enough for the human eye to perceive them as a continuous, fluid motion. Fowler adds, “While higher frame rates provide a more realistic, lifelike image, 24fps has a dreamlike quality that audiences have come to associate with storytelling in film.”

One of her collectors is the revered cinematographer, Seamus McGarvey.

Known for his work with directors from Lynn Ramsey to Joe Wright, he sees Fowler as a true visionary. “I love the liminal space between the star shine of cinema and the phantasmagorical trace of that glamour. I love Nina Mae Fowler’s work and how her art simultaneously depicts flickering, gilded, projected dreams with lonely disappointment.”

Each one of us wears our tribulations on our faces - our divorces, our health woes, our battle to both parent and excel at work, our heartbreaks, career disappointments and loneliness. The tribulations are more visible in the case of the celluloid star because the canvas given to work with is simply more expensive and expansive than our own.

There is an argument that the upsetting pictures that make the cover of The National Enquirer are not akin to the work of the misguided parishioner, rather they are outsider art the once great star makes out of themselves. On Fowler’s studio wall hangs a notorious 2010 cover of the tabloid, multiple troubled stars arranged under the headline: “Who’ll die first? Find out inside!” It’s a cover that blunts both dignity and surprise (really, the rudest thing you can say on someone’s death being “I told you so”.) And across from it, beneath, beside and in spite of it, hang Fowler’s meticulous and generous works of restoration.

About the author

A writer and director, Emma Forrest has had five novels published and two critically acclaimed memoirs. She has developed numerous film and television projects with companies including BBC Films, Film4, and BBC America. Her directorial debut, the LA-set feature Untogether, starring Jemima Kirke, premiered at TriBeCa in 2018. She currently lives and works in London, frequently contributing to The Sunday Times and The Guardian alongside developing series for television and film adaptation.