Luminary Drawings

Dame Marina Warner

Featured in Ruined Finery, 2020

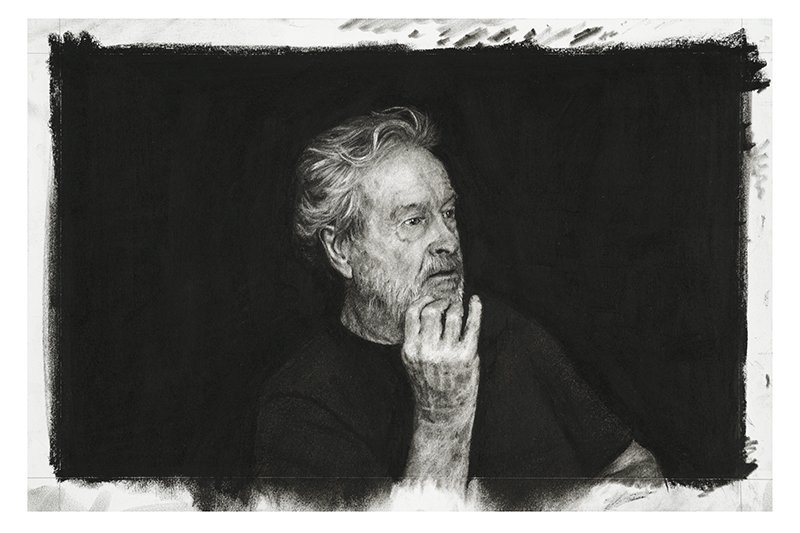

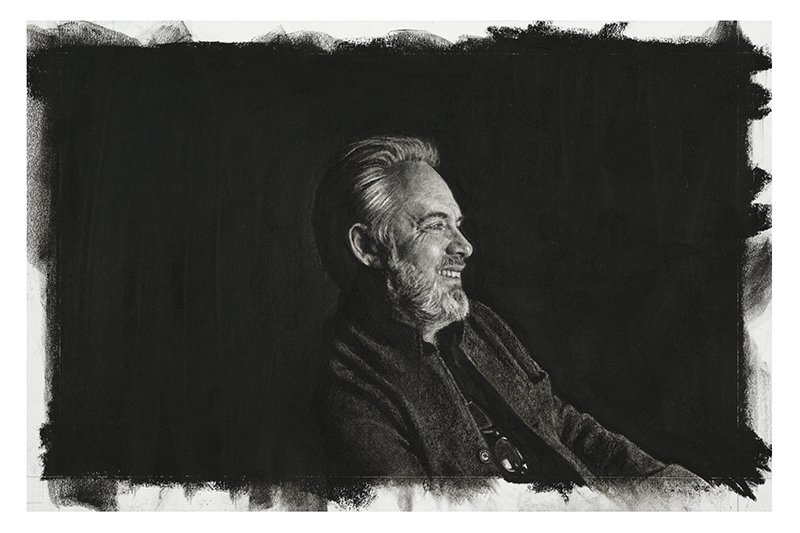

Luminary is a perfect word to describe Nina Mae Fowler’s sequence of film directors’ portraits. Her subjects are leading lights who aren’t very often in the spotlight, but stay behind the scenes: esteemed film directors, several of them cult idols of the industry, they represent its variety and range – thrillers, animation, documentary, political drama, blockbusters, noir. Cinema is a luminous art, made of a play of light and dark, of shadows or cast projections – ‘filtows’ or light-filled transparencies in motion. For the sittings, the faces of the portraits’ subjects are lit only by projection on to a screen; they materialise out of the surrounding darkness; each director is enthralled, watching a favourite film. Absorbed into the act of watching, they lose all self-consciousness at being looked at for the purpose of a portrait. It inverts the usual relationship of directors to audience: they have become the object of the gaze and we the delighted voyeurs. We see Sam Mendes chuckling, Sally Potter pensive, Ken Loach alert in his appreciation, Nick Park paying close attention, analytically. They’re so entranced, we’re caught up in their feelings, and their expressions have been so sensitively registered by the artist that we too become lost in looking at how intently they are watching. Nina Mae was watching and filming them during the screenings – which the French call séances, and her idea for the sittings did indeed help her tap into her sitters’ inner feelings, mediumistically. It was a subtle and sensitive – and very clever – mise-en-scène that Nina Mae Fowler devised.

The medium of pencil drawing, as practised by Nina Mae Fowler, from her finely sharpened hard pencils (4H - 9H) like silverpoint to her brooding sooty blacks, with her frequent use of erasure to add lights to the image, remembers the silver nitrate printing palette of early Hollywood and to the film noir which she’s explored in early series of expressive montages of film stills. There’s a moody effect of moonlight, a nocturnal note that’s deepened by the secrecy of each film director’s choice of film to view during the sittings, and the smudgy unfinished borders hint at the movies, reminding us of the process unfolding over time, mark by mark, erasure by erasure, as if frame by frame. The portraits are living likenesses – something that isn’t always a quality of contemporary works – packed with inward character and not only outward resemblance.

Luminary Drawings is a sequence that pays tribute to a national art – and industry – that is underrepresented in the National Portrait Gallery. Significant national figures are depicted in the collection to build a record of the country’s history, cultural and social, but money for commissions is tight, of course. In the queue of possible subjects, Prime Ministers and Royals and mega-stars take precedence. Subjects from a category such as film directors, who aren’t famous or visible like an actor or an athlete, usually have to wait to enter the collection for someone to donate a portrait or offer an existing image at a good price. And the results become very miscellaneous as a result.

When I was appointed a Trustee in 2008, I suggested that some of the worst gaps in the story of the nation’s culture might be filled if the Gallery commissioned drawings rather than full scale oil paintings. I am a great admirer of drawings and feel that drawing shouldn’t be considered a lesser artistic form, and it really shocked me that artists like Nick Park, whose Wallace and Gromit series meant so much to a whole generation and whose Aardman studio is a national treasure, or another supreme creative original like Sally Potter, were not even represented in the Gallery’s photographic archives. The then director of the NPG, Sandy Nairne, and the senior curator Sarah Howgate agreed and the idea was approved. I was very kindly asked to join them to choose the artist from a small number invited to submit ideas. It was the first time I met Nina Mae Fowler. She showed us her dramatic compositions inspired by film noir and Hollywood scandal and talked with lively knowledge and love of film. Her interest in how images are staged, how actors so powerfully take possession of our imaginations and embody our fears and fantasies, her technical inventiveness and her expressive responses made our decision very easy.

After Nina was selected for the project, she faced a formidable task. I had been entirely mistaken to imagine a series of drawings would be quicker and less arduous than a portrait in oils. Several years rolled by as the trustees debated which film directors should be chosen to sit (by the time the list was finally decided I had come to the end of my term as trustee). Then the negotiations with the directors themselves began. Busy people, they were naturally elusive, and throughout, the artist showed tremendous tenacity and good humour as she travelled up and down the country – even going to New York – following on her subjects’ trails.

The bold drama of Nina’s monochrome tableaux in Measuring Elvis and her relish for cinema’s scenes of passion and mayhem, for divas’ flamboyance, glamour and tragedy, has been replaced here by a quietness and intense interiority. The studies of individual faces have a Netherlandish quality of fine-grained close-up scrutiny, as in a Dürer drawing, with the greater sympathy of Memling or Jan Gossaert. But whereas such Old Masters suspend their subjects into a timeless meditative stillness, these portraits remember the intrinsic character of her sitters’ medium – the movies – as the artist conveys the expressions flickering in their eyes or puckering their brows as the light from a film moves reciprocally across their faces.