Stage Door

Victoria Myers

2021

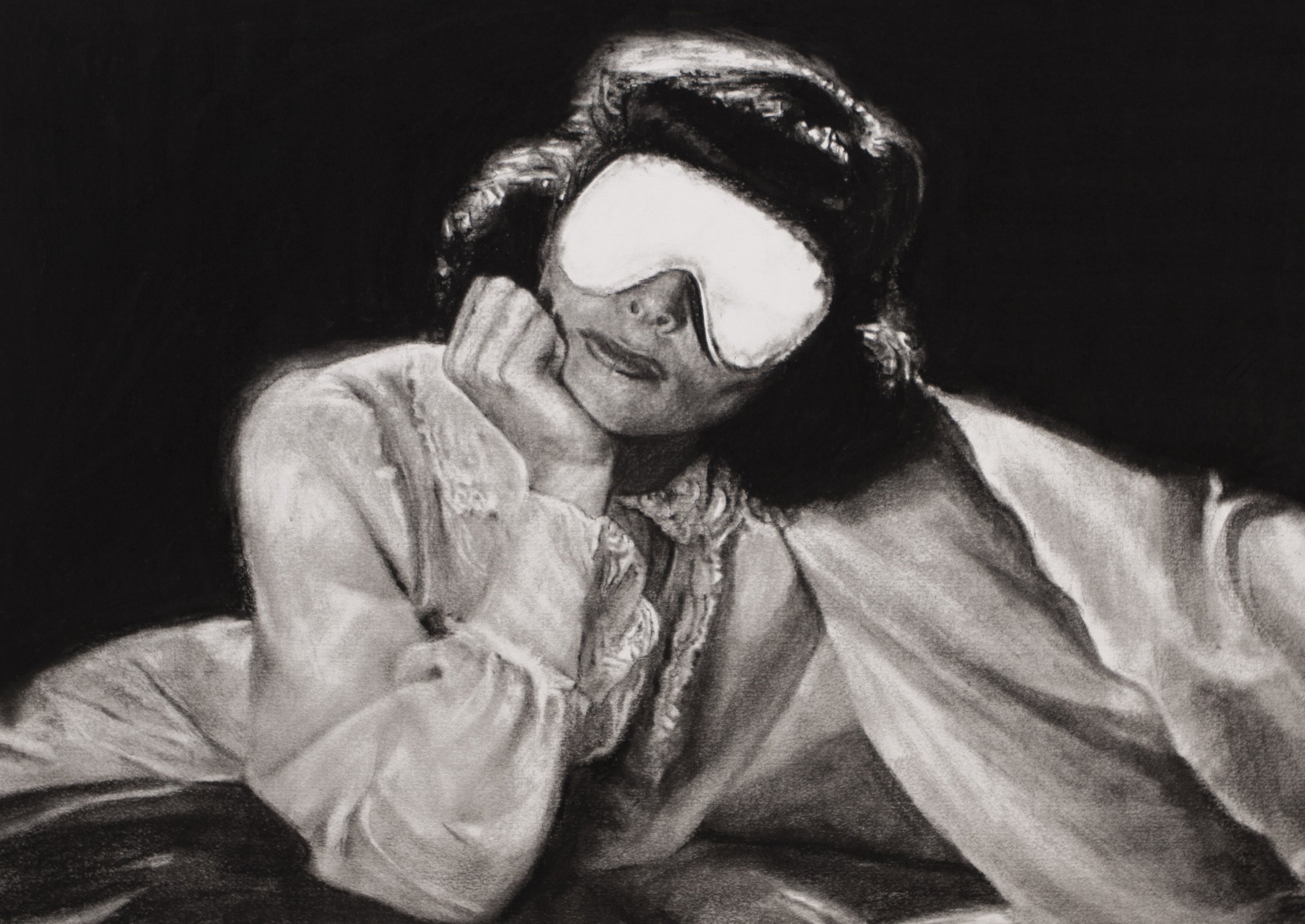

Screen Door, Nina Mae Fowler, 2021

When I was in my twenties, I hung around a number of actresses in the theatre. It all seemed very exciting, but none of them seemed very happy. As a child, I loved movies about actresses like the 1937 film Stage Door, about a group of aspiring actresses at a theatrical boarding house for women in New York City. I thought the women, with all of their fast-talk and tribulations, seemed the height of glamour. Watching the film again as an adult, I saw that, even in the movie, nothing was uncomplicated and without contradiction.

Stage Door, originally a Broadway play, was acquired by RKO Pictures and seen as a potential vehicle for Katharine Hepburn, who no one knew what to do with, and also for Ginger Rogers, who no one knew what to do with when she wasn’t doing everything Fred Astaire did but backwards and in high heels. For the film, the director Gregory La Cava dramatically changed the story from the Broadway version. He assembled a large cast of actresses and, to give the film a more authentic flavor, utilized wide shots, showing the actresses in their cramped and chaotic boarding house. Large portions of the script were based on improvisations during rehearsals. Throughout filming, no one knew how it was going to end. All of this contributed to making Stage Door a complicated portrait of young, ambitious women.

The women in Stage Door are loud—they laugh loudly, they are quick with a witty remark, and they talk a lot—about jobs, auditions, and always about dinner. Given the sheer amount of dialogue, it is impressive how very little of it is about men. The women throw their bodies around—up and down the stairs, legs flopping onto sofas, arms gesticulating into the air. This is not a film with a lot of crossing at the ankles.

At the center of it all are Hepburn and Rogers. Hepburn plays the new girl, an heiress-in-hiding who wants to rough it with the working class, and Rogers plays the spunky working girl. Assigned as roommates, they approach things from vastly different life experiences and are immediately at odds. Over the course of the film, they both encounter the same lecherous producer. When he approaches Rogers, she has no choice but to acquiesce to being his date. If she doesn’t, she knows she’ll lose her much-needed job. She soon finds her curiosity piqued by the close up view of the glamorous life of fame and fortune that he offers. Hepburn rebuffs him. She’s never had to worry about jobs or money. She’s seen the glamorous life. And, besides, unbeknownst to her, her father has bought her the lead part in the producer’s new Broadway play—a part another woman at the boarding house desperately wanted.

The central clash in the film between Rogers and Hepburn involves the producer, with Rogers believing that Hepburn has stolen him from her, and Hepburn believing that she’s teaching Rogers a lesson—but then it takes an unusual turn. The real central conflict is not about a man, but a job. When Hepburn’s father buys her the part in the Broadway play, the actress who wanted it is so devastated and so rundown that, hours before Hepburn’s opening night performance, she kills herself. Rogers, full of fury, confronts Hepburn, accusing her of being responsible for the death and daring her to continue in the role. Hepburn does go on with the show, but ends it by dedicating her performance to their dead friend. Then, forgoing the opening night party, she and Rogers go together to the morgue.

Screen Door III, Nina Mae Fowler, 2021

But in Nina Mae Fowler’s images, Screen Door, none of that has happened yet. Not the producer, not Broadway, and not the morgue. Fowler’s images depict Hepburn and Rogers early in the film, in their tiny, stuffy room in the boarding house. Against a black backdrop, they are in dialogue, but also alone. They are wary and full of assumptions about the other, yet also curious. They are in that stage of life when one wants to both assert one’s identity and try on others. Underneath their lipstick and styled hair, they are very young. There is something about old Hollywood movies that makes us forget how young some of these women were. Hollywood may have suspended them, untethered, in the firmament of The Leading Lady (at least until they were too old), but Hepburn was barely 30 while filming Stage Door and Rogers only in her mid-twenties. In Fowler’s images, we are reminded that they are young women trying to figure out the world around them, only without access to the whole picture.

In the film, New York, the city that holds so much promise, appears only through windows. It comes crashing through the girls’ bedroom in the form of a neon sign

(that’s what the eye masks are for, explains Rogers) but the full view of it—Manhattan in all its brightly-lit glory—is only seen through the window of the producer’s apartment. He gets to be above it—they’re at eye level. A lot of being young is trying to put together the puzzle of the world around you, which is so often only seen in pieces. The women who populate Stage Door are still trying to figure out who they are as people, and how to navigate the rocky ethical terrain of the professional world with its shifting scales of compromise and complicity, and the push and pull between the way the world is and the way they each want it to be.

The film ends with one of the aspiring actresses (played by Lucille Ball) leaving to get married. Hepburn and Rogers sweep her over the threshold and off to her fiancé and the journey back to her hometown. It is not a happy ending; she does not particularly want to go. But she’s not getting anywhere as an actress and marriage means financial security. After she leaves, in the final moments of the film, Hepburn and Rogers get on with things. A new actress arrives. The world keeps going.

As a film, Stage Door contradicts itself. It lacks a totally coherent through line, which even if structurally flawed, makes it true to the vicissitudes of life. I don’t know if Hepburn and Rogers are actually best friends at the end of the film. But as Fowler’s images remind us, maybe instead they are that other type of person you need when you are young— the one who validates your experience, adds another piece of the puzzle, and who helps you keep going.