-

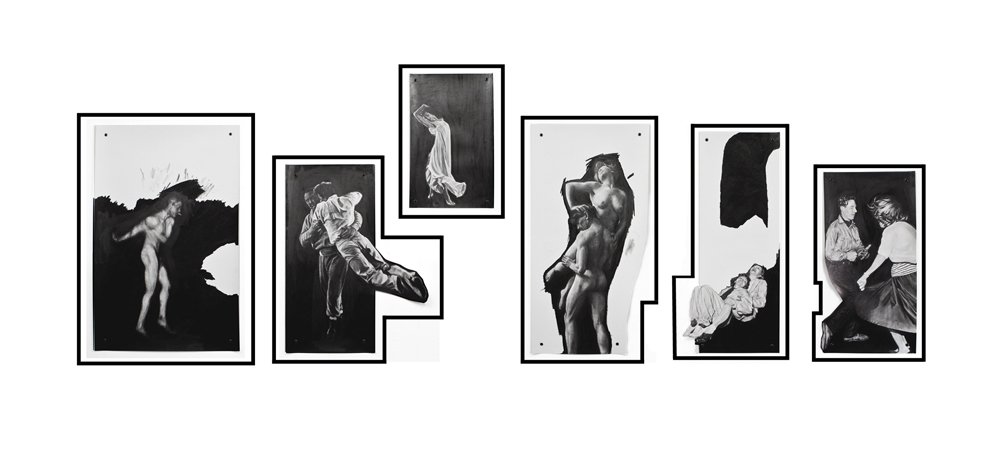

SHE SHOULDA SAID NO

But she didn’t. And neither did we.

These drawings ask us to dance. They invite our imagination to fill in the gaps, concentrate on a freeze frame from the past and in doing so live completely in the moment we have with each image. The inanimate figures are so close to the people they depict, now old or long dead, that they use our association with film to stimulate a familiar suspension of disbelief. These drawings are breathing, laughing and living in one infinite moment. Fowler and the dancers are making energetic marks to describe a human state in non-verbal communication, in which the body is the tool and the subject. Her mark-making guides their bodies into movement, establishing a duet between dancer and artist; the retention of unfinished spaces suggests that there is more to come. The work refuses to be boxed by the regular 1,2,3,4 of a frame, stretching instead — limbs kicking — into the unknown. The way in which the frames follow the bodies of the protagonists makes them all the more physical, demanding to be held on their own terms. The title of the series is taken from the film She Shoulda Said No (directed by Sam Newfield). Made in 1949, this was essentially a piece of propaganda warning Americans against the dangers of marijuana. Based on the real story of the film’s leading lady Lila Leeds, the screenplay follows a young woman on her journey of self-discovery and survival. However, like Eve before her, the character is made an example of within a patriarchal construct, holding her responsible for a downfall. Fowler’s drawings keep downfall at bay by suspending the ecstatic moment outside of reality, repercussion or responsibility and focus on their innocent revery. The drawings have caught the protagonists in the process of testing their boundaries and learning from the highs of experience.

Featured in Measuring Elvis, 2015

Read further writing and essays in response to the subjects and themes relating to the work of Nina Mae Fowler here.