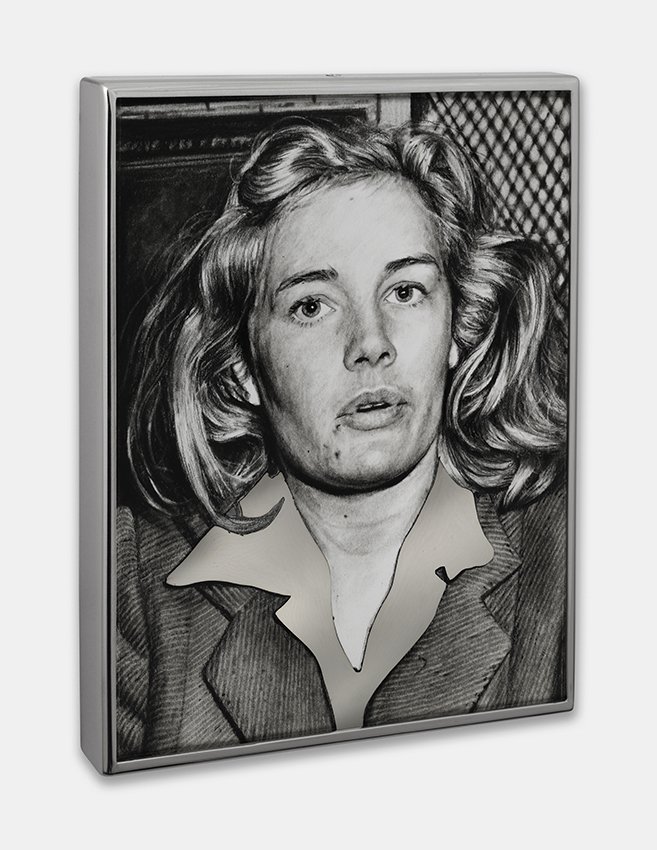

Una Pecadora Sin Cara (A Faceless Sinner)

Austin Mutti-Mewse

Writer, illustrator and published author

Featured in Ruined Finery, 2020

There were those who longed for fame but didn’t make it. Those who made it and lost it – failed marriages, faltered careers and false friends. There were platinum blondes and raven-haired goddesses who died before the wrinkles and lines of which Hollywood lived in fear had a chance to set in to their Venus-like faces... and there was Frances Farmer.

The light bulbs that surrounded the make-up mirrors in the dressing rooms at ‘her’ studio, Paramount Pictures, Hollywood, would flicker. Erstwhile movie starlets in old age commented to me on the haphazard nature of the electric current. Fully operational, fully burned, they gave the artist the impression of being on stage. An uneasy sense that each lambent bulb ignited a torch paper which in turn triggered a different emotion. As if one’s soul had become somehow opaque – laid bare. With only light and no shadows, the mind is permeated.

No more secrets. No more lies. But no truths either. For this was Tinsel Town, this was Hollywood. The ‘City of Angels’ where the gloss can so easily turn to dross.

Frances Farmer sat in front of many such mirrors. Frances Farmer was a starlet who became a Hollywood star. She was plucked and preened to such a degree she failed to recognise herself. She faced the cameras, she faced directors, she faced criticism and she criticised. Frances received applause and disapproval in equal measure from audiences who watched her in darkened movie theatres. Few rose so fast and fell so fast as Frances. Up there on the screen there was no hiding place. Hollywood made it that way.

Fiercely independent, the Seattle beauty became the ‘Golden Girl’ in Clifford Odets’s Golden Boy. A star of stage and twenty Hollywood films, she appeared on the surface to have it all. But the cracks ran deep.

Chief among ‘victims’ of the Hollywood machine, Farmer’s family, friends, co-stars and co-workers commented that she exhibited signs of psychosis, fuelled by a dependency on alcohol, from the get-go.

As the series of Nina Mae Fowler’s artworks show, Frances is determined, she is brazen, she is scared, and she is damaged. Each piece a window on the person behind the persona.

Well known for struggling with mental health, Farmer spent years being institutionalised – yet against all odds, she survived.

As art imitated life, the downward spiral of Frances Farmer became something of a masterpiece. The crescendo, a much-mentioned lobotomy. It was a fabricated yarn that became the basis for the 1982 feature film Frances, starring Jessica Lange, and a source of inspiration for the troubled Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain.

Nina Mae Fowler’s art is like a peering into a looking glass into another world. A world that for Frances Farmer should have been one of make believe, a journey over the rainbow.

The myths and legends that follow Frances Farmer still captivate audiences’ imaginations. The untruths eclipse her actual body of work. Her life thereafter – though irreversibly scarred – was lived.

Fowler has captured a moment. A series of works that, fifty years after Farmer’s death, beg the question: ‘what happened next?’

A fellow actress and contemporary also under contract to Paramount Pictures at the time commented to me on her own experience in Hollywood. “What we earned was a living. What we gave was a life!”