Last Pictures

Alissa Bennett

Writer, independent curator and gallery director

Featured in Ruined Finery, 2020

The last known photograph of a pre-disaster Titanic was taken off the coast of Ireland on April 12, 1912, three days before the vessel struck an iceberg and famously sunk to the bottom of the ocean. In spite of its renown, there is nothing particularly notable about this image, no formal detail that I could provide that might distinguish it from countless other depictions of Gilded Age ships slipping across silver seas. The air of psychic doom that flickers quietly beneath its surface is activated only by our understanding of the fatal catastrophe that lurks in the distance, by our knowledge that the reaper’s scythe is poised and ready to swing just beyond the edge of the frame.

We play a subconscious game of violation every time we search images like the one described above, for while the eye may scan the contours of the hull or scrutinize the water for signs of disruption, what we actually want to see cannot be found in the composition. Titanic, like all ill-fated starlets, inspires in her devotees a particularly predatory type of looking, a gaze more inclined towards penetration than passivity. This compulsion to trespass is situated at the core of fandom itself: we want to look inside; we want to peel back the veneer; we want to wander through decimated cabins and ballrooms that we were never invited to enter in the first place.

This desire to get closer is certainly one of the more transgressive expressions of celebrity adulation, but I would suggest it is not an uncommon one. Though we naturally differentiate our lust for symbolic proximity from the machinations of the stalker, many of us regularly breach the barricades that are meant to quarantine the private lives of the famous from the public sphere. Scandalous Hollywood legends, tell-all biographies, gossip websites and blind items are all designed to satisfy a rapacious cultural voyeurism: barred from access to the real, we greedily accept sensationalism in its stead.

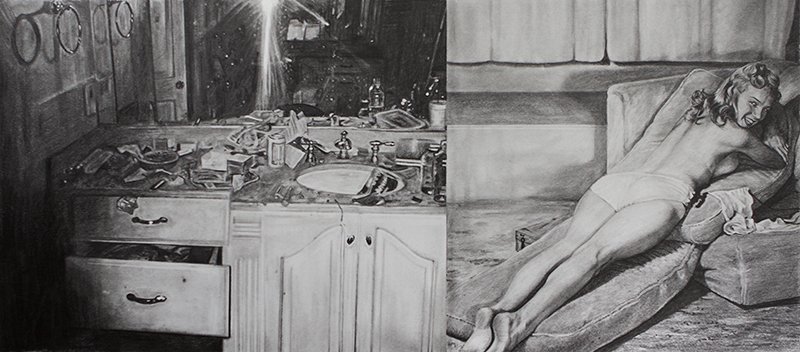

Artist Nina Mae Fowler reminds us that there has always been a cannibalistic bent to our interest in celebrity. A sumptuously rendered still of Judy Garland seems to document a moment when the entertainer has momentarily dropped her performance, her face registering the full impact of the pain wrought by a lifetime of public scrutiny. Juxtaposing an image of a young and coquettishly stripped-down Marilyn Monroe with the infamous snapshot of Whitney Houston’s bathroom-cum-drug den, Fowler intimates a ‘choose your own adventure’ story that inevitably terminates in the mortuary. Remembered more for her arrests and institutionalizations than for her success as an actress, Fowler memorializes Frances Farmer as a victim of our corrosive curiosity, a disheveled madwoman long divorced from the brief flash of her stardom.

Cognizant that the cults of fame and death travel too closely to one another to avoid occasional intersection, Fowler’s work consistently probes the connective tissue that binds glamor to degradation. It is often our hunger for more, her images consistently suggest, that instigates a predictable collision course with ruin, the impact of our fascination inflicting a reliably fatal injury. I recently told Nina that her drawings always remind me of ‘The Oval Portrait’, Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘double’ short story about a young woman whose artist husband becomes so obsessed with documenting her beauty that he fails to recognize he has killed her in the process of painting her. The story, which concludes with the husband remarking in horror at the life-like qualities of the portrait, has always struck me as an apt metaphor for the vampiric nature of our desire. There is a similarly uncanny quality that vibrates through the surfaces of Fowler’s works, a strangely human affect that collapses the distance between subject and object, between celebrity and fan. Finally afforded the opportunity to exchange glances with our long-gone idols, we find ourselves mute; the weight of our complicity has left us with nothing to say.

The final official photographs of Marilyn Monroe were shot for Life magazine by Alan Grant on July 4 of 1962. Taken in her home one month prior to her death, the images are not dissimilar to hundreds of others that document the actress doing her best to summon her bombshell alter-ego from the ruins of her personal and professional lives. Perched on a chair in front of a window, Monroe goes through the gestures of performing pluck and wistfulness and playful sex appeal, occasionally hitting her mark but often falling just short of it. An examination of these photographs unearths nothing new. There are no clues or messages, no great revelations to be made, no lingering questions that can be suddenly resolved, though none of that stops us from looking. In November of last year, the Hollywood auction house Julien’s sold the chair that featured in this series for $81,000. The lot notes explain that the actress damaged the object in the course of her afternoon with Grant, a detail I assume only increased its desirability for those compelled to locate the trace. I wonder if the Grant photos speak differently to whomever ultimately bought it, if its transposition from surface to space brings them any closer to a woman now dead for nearly sixty years. It is, I suppose, the ultimate puncture, the perfect way to enter into the last picture.