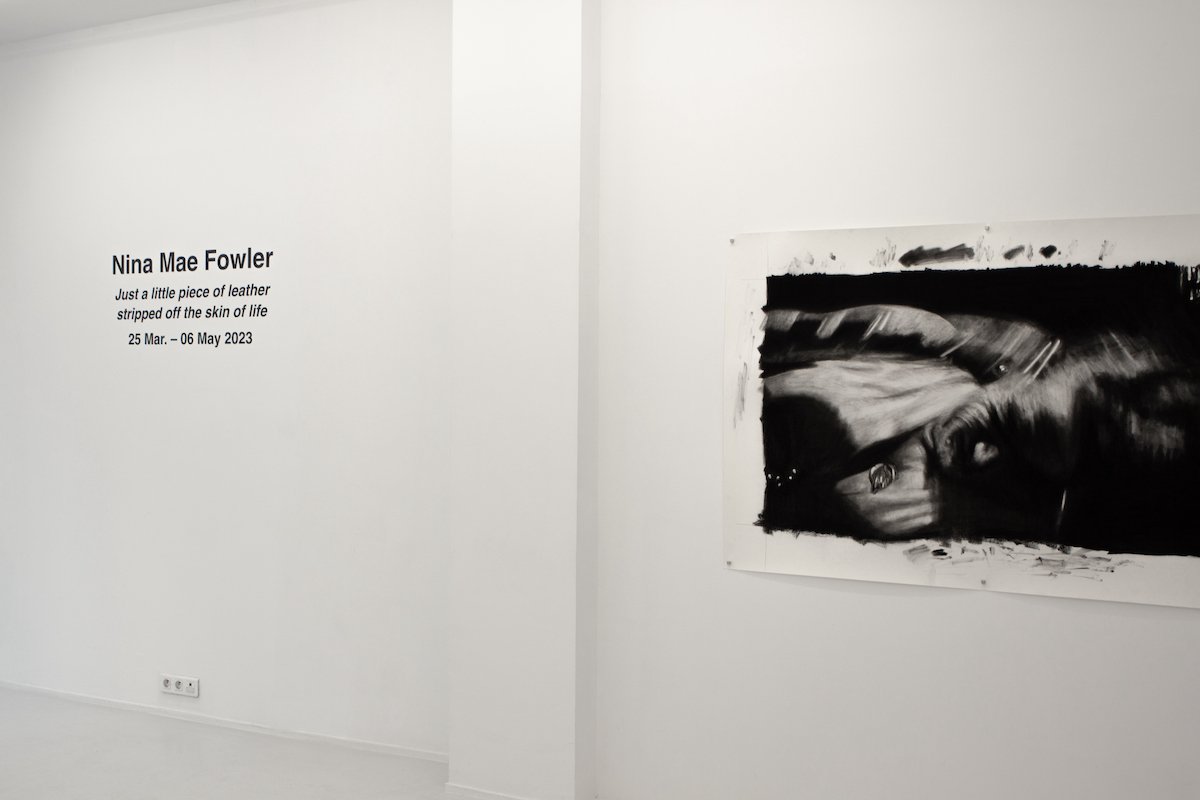

JUST A LITTLE PIECE OF LEATHER STRIPPED OFF THE SKIN OF LIFE

SUZANNE TARASIEVE | PARIS, 2023

25 March — 6 May 2023

7, RUE PASTOURELLE

75003 PARIS

This exhibition represents Fowler’s inaugural show with her Parisian gallery, for which she created over thirty new pieces. The exhibition also includes a body of work made in collaboration with Marlene Dietrich’s granddaughter-in-law, Wendy Riva. The series, ‘an end to a kind of loneliness’, showcases new works and an artist’s publication, made in response to an archive of photographs and letters exchanged between Dietrich and her grandson Michael.

-

The title of English artist Nina Mae Fowler’s solo exhibition, “Just a little piece of leather stripped off the skin of life,” is borrowed from a note handwritten by Marlon Brando, one of cinema’s most celebrated icons, at the Elysée Hotel in New York. Inspired by the American actor’s poetic message, Fowler connects it to her latest series of drawings, whose themes examine celebrity, fame, sexuality, and secrecy.

Trained in sculpture at the University of Brighton, Fowler is best known for her black-and-white drawings. Fascinated by Hollywood’s Golden Age from a young age, she has developed a powerful practice dealing with female archetypes, particularly those of actresses in Hollywood culture. Using archival press footage and scenes from classic movies, Fowler works on the construction of images, accentuating the cinematic rendering of her works. As in an editing room, she rewinds, pauses, and edits obsessively, confidently taking details from different stills and assembling them on paper.

Taking a close look at the sometimes ephemeral and dazzling heyday of Hollywood’s beloved icons, the artist addresses binary themes of fear and desire, tragedy and heroism, light and darkness, beauty and ugliness. Accurately and meticulously crafted, Fowler’s drawings examine our fascination with often borderline public figures, worn down by the Hollywood system and the tabloid press. This relentlessness is captured in the series of touching portraits of Rita Hayworth, photographed by paparazzi as she disembarked from an airplane after suffering a bout of dementia during the flight. Her hair disheveled and her eyes haggard, the actress seems to be somewhere else, lost. In her new series A Little Piece, Fowler evokes the personal history of Jean Peters, Howard Hughes’s second wife, focusing on the emotion of a film excerpt in which the actress, prone on the ground, is splashed in the face with a glistening liquid. The couple’s sad daily life (due to Hughes’s mental illness) cannot be extracted from Peters’s distress, as captured by Fowler. This deconstruction of the gaze takes place through assemblages that give a new face to the actress, at once a source of dread and delight.

Fowler’s technical mastery allowed her to bring together Marilyn Monroe, Bette Davis, Jayne Mansfield, and Marlene Dietrich in a large-format drawing that became famous, Every girl crazy; this time Fowler creates more intimate images, accentuating the sexualization of the characters or revealing their weaknesses. Alternating large and medium formats in her new series, the artist brilliantly orchestrates her work in graphite as she shapes the clay of her sculptures, to create a tangible and tactile tension in these new faces. These icons become living, vibrant, happy or unhappy women, as in the Love Mass series in which we discover a maternal and loving Marlene Dietrich, far from the glamour for which she was known.

Fowler’s monumental compositions thus form a continuation of classical history painting, where gods and goddesses are replaced by rock and movie stars. Raised by the paintings of Courbet and Manet, Fowler searches for the hidden face of events. Her stylistic vision delights us, even as her subject matter infuses a dark and devastating truth, as evidenced by the darkness and torment of the soul that remains central to her subjects. “Without contraries there is no progression. Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate, are necessary to human existence.”[1]

Faced with Fowler’s drawings and sculptures, more enigmatic than they appear at first glance, we must unravel a hidden narrative, as powerful as any ancient myth or legend.

Béatrice Andrieux

Curator and critic

[1] William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1790